This is Part 5 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

In our Building a Better Density Bonus series we’ve covered a range of concepts and recommendations for increasing the amount of affordable housing in Los Angeles at minimal public cost, but we’ve saved the most innovative (and, in our opinion, best) idea for last.

Generally speaking, what we’ve talked about so far is how to create more affordable housing from new construction. In a city with over 850,000 renter-occupied housing units, however, we’re missing a huge opportunity by focusing almost exclusively on the approximately 15,000 new units built each year (most of which will necessarily be market-rate anyway). What if we opened up our existing housing stock for use as affordable housing?

Done right, we can use the density bonus to increase the supply of market-rate housing while also raising funds to subsidize affordable units in existing multifamily buildings—all at much lower cost than the current new-construction-only regime.

Proposal: Create an alternate fee-based density bonus program; use these funds to subsidize units in less expensive market-rate buildings.

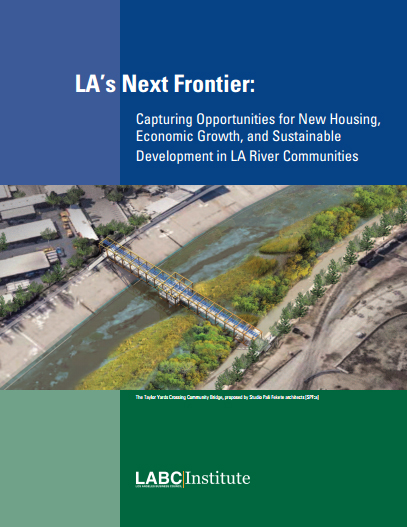

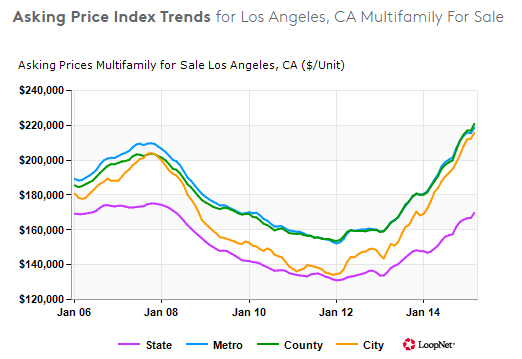

According to data from 2011, the average cost of new affordable units peaked in California in 2009, at $334,000 per unit, and fell to $260,000 by 2011; due to rising land values and construction costs, the current cost of affordable unit production in LA is likely greater than $350,000 per unit. By comparison, the median asking price for a multifamily unit in Los Angeles is currently under $220,000.

To take advantage of this cost disparity, Los Angeles should develop a program to acquire older (but still safe and livable) multifamily units with fees paid in lieu of on-site construction of affordable housing. Instead of providing on-site affordable housing at $300,000 or more per unit, developers could pay into a fund—say, $200K-$250K, or even higher for more expensive projects—that would subsidize a greater number of affordable homes in nearby, currently market-rate buildings.

This program would have a number of benefits:

1. Density bonus developments would create more total affordable housing—potentially much more, depending on how the fee is structured—by spending in-lieu fees on less expensive properties.

2. If the fee is reasonable it should encourage increased participation in the density bonus program, further increasing the supply of both affordable and market-rate units at no public cost. This program would be especially appealing to smaller-scale developers (10 to 50 units) for whom the hassle and cost of managing just a few affordable units often exceeds the value of additional market-rate units.

3. By buying new units outright, the city (or its agent) could hold these properties in perpetuity. Affordable units are currently covenanted for 55-years in California, at which point they revert back to market-rate—that would not be necessary under this proposed program.

4. Because these acquisitions are permanent, they become an asset that can support additional affordable housing acquisition/conversion in the future. With minimal support this program could become relatively self-sustaining and grow exponentially: one paid-off building can support the acquisition of several more developments, each of which can support even more acquisitions as they are paid off, on and on, forever.

To be clear, this is not an entirely new idea, it’s just a good one: The Connecticut Housing Finance Authority launched an initiative a few years ago to provide favorable financing to investors who wanted to purchase or refinance existing market-rate developments, as long as they convert a share of them to affordable housing. Largely funded by federal HUD grants, the Zollie Scales Manor apartments in Houston were renovated and made affordable to households earning less than 80 percent of area median income. Drawing from a variety of funds, including in-lieu density bonus fees, Los Angeles could implement a similar program on a much grander scale.

IMPLEMENTATION

Because an acquisition-based affordable housing strategy would be such a dramatic departure from current policy, a range of implementation issues would have to be addressed.

Equity

For one, it would be important to structure the program so that it increased the total supply of both affordable and market-rate housing. Without such a framework in place, we’d be dealing in zero-sum trade-offs in which every new affordable home is one less market-rate unit; as more low-income renters gained access to affordable housing, the pressure on market-rate units would increase and drive rents ever higher for middle income Angelenos. This is where the density bonus comes in handy: by allowing for an in-lieu fee program, funding for the acquisition of existing buildings and conversion to affordable housing is directly tied to the production of housing beyond existing zoning limits.

It would also be important to ensure that units purchased with density bonus fees were in close proximity to the new developments that produced those fees, to avoid creating islands of poverty. In most cases this should not be difficult to achieve, since development in LA has been focused in relatively densely-populated neighborhoods with plenty of existing housing stock—places like Hollywood and Koreatown in particular.

Financial

It might be desirable to purchase entire buildings but set aside only a share as affordable to further prevent concentration of poverty at the individual building level; the market-rate units in such a building would also help to further subsidize the affordable units. Using a quick and dirty financial analysis, we examined a hypothetical building purchased for $250,000 per unit, setting aside 20 percent of its units for low income residents, at rents of $800 a month. We assumed that in-lieu fees would be used to support this venture by paying down loan interest costs in early years, reducing the effective interest rate from 5 to 2 percent, with market-rate units contributing a larger share of interest payments over time.

We found that, in a 100-unit building with an average market-rate rent of $1,500 and 20 percent of units rented to low income families at $800 a month, $500,000 in in-lieu fee subsidies would be required in year 1, shrinking to $400K by year 7 and $300K by year 10. By year 18, the building would be completely self-sustaining, having received a total subsidy of $5.5 million*—all of which is derived from in-lieu fees paid by private developers. In the years that followed, the property would continue throwing off revenues that could subsidize additional acquisitions and interest payments for other affordable properties. At the conclusion of the 30-year loan term, the property could be refinanced for major capital expenditures (including renovation), or simply use its annual profits to continue subsidizing an ever-greater number of affordable units in the city. Rather than allowing the long-term value of these properties to be captured by private owners, it would be retained by community members in the form of a balanced supply of mixed-income housing. Traditional affordable housing grows less valuable to the public over time, as the years run out on their covenants and they prepare to be converted back to private, market-rate use. Properties acquired and managed under this new program, by comparison, would only increase in value as their loans were paid off and revenues were used to reinvest in other affordable housing projects.

Governance

Developing a governance structure that was free of political influence and insulated from the local government to the greatest degree possible would be extremely important for a program of this nature. Property acquisitions and management could be handled by a economic development corporation or other non-governmental organization, for example, with the local government serving primarily as a pass-through for affordable housing funds. This would shield the public sector from getting too directly involved in private real estate market interventions, and would allow operational decisions to be made with minimal political interference. Ideally, it would also ensure that the short-term thinking endemic to many political groups did not affect the long-term mission and vision of the non-profit housing organization.

Being the most complex proposal of our Building a Better Density Bonus series, creating a program like this would undoubtedly be a major undertaking. That said, in an era where our approach to affordable housing is often piecemeal, inconsistent, and woefully inadequate, this serves as a counterpoint with the potential to be truly transformational. We hope LA leaders will seriously consider its implications, and we’re happy to join the conversation and see what can be done to increase the supply of affordable housing in our city!

Thanks for reading!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

*We should also note that this analysis is very conservative, assuming market-rate rents increase at just 3 percent a year and that affordable rents remain essentially unchanged throughout the 30-year period, and that in-lieu fees are the only financial subsidy offered to the project—in truth, it’s entirely possible that such a program could also secure any number of grants, incentives, and rebates, all of which would further reduce direct subsidy costs to the city.

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.