This is Part 3 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

In the last installment we discussed our first recommendation for density bonus reform: Reducing the affordable unit requirement for individual projects, and tying this change to clawback provisions on development projects that exceed profit expectations. The underlying rational for this recommendation is that, for every developer who chooses not to participate in the density program (or doesn’t take full advantage of it), the city is losing out on hundreds of thousands—even millions—of dollars in private investment in affordable housing. Lowering the threshold for participation may decrease the value of this investment on a per-project basis, but total private investment will increase as more projects participate in the density bonus program.

Our next proposal builds upon this idea, recognizing that, for many developers, participation in the density bonus program is a marginal decision—that is, relatively small amounts of money often make the difference between constructing the maximum number of affordable units or constructing none at all. This is something of an “in for a penny, in for a pound” situation, where if you’re willing to go through the density bonus process, you might as well go for the whole bonus in order to spread out your land costs over the largest number of units possible. Providing financial incentives to push developers toward the “build the maximum number of units” side of the ledger can, in some circumstances, be a low-cost means of increasing the supply of affordable housing, and should be considered when other options fall short.

Proposal: Fill funding gaps in density bonus project budgets with public sector funds, when necessary, to maximize private investment.

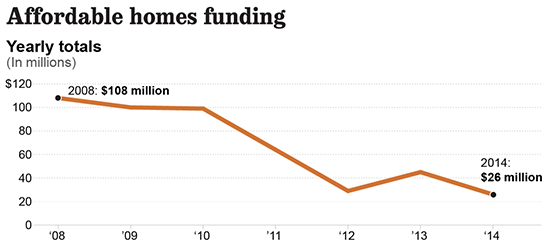

According to the Housing and Community Investment Department of Los Angeles (HCID), the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund allocation has fallen 75 percent since 2008, from $108 million to just $26 million per year, largely as a result of the dissolution of CRA and declining federal funds for low-income housing. The number of affordable homes that can be funded by the department has similarly declined, from 1,200 to approximately 250 units per year—far, far below the anticipated need of 82,000 new affordable units by 2021. That $26 million, at 250 units per year, means that HCID is spending an average of about $100,000 per unit, leveraging that investment to secure the remainder from other government and private sources. Not to disparage HCID, but we think it may be possible to leverage that money even further by filling gaps in projects that would like to participate in the density bonus, but can’t quite afford to.

If a developer’s financial analysis shows that the profit earned on bonus market-rate units can cover just $300,000 of the $350,000 cost of each affordable unit required to receive the bonus, for example, they probably will not build those affordable units. (Like any other business, developers that knowingly commit to money-losing ventures will probably not be in business for very long.) In such cases, the city should consider how it can help fill that gap and lay claim to the $300,000 of private investment that the developer can support. This may irk some individuals who consider this a giveaway to private developers, but the alternatives are far less appealing: using the same public funds to build the units at their full $350,000 cost*, or using them to leverage a very limited amount of state and federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit dollars. Spending $50,000 or less subsidizing affordable density bonus units would effectively double the leverage ratio of city housing expenditures and get us twice as much affordable housing for the money.

In a recent conversation with Allan Kotin, it was pointed out that low interest rates may also be playing a role in the limited density bonus participation of recent years. Under the 80/20 Housing Program, developments with at least 20 percent of their units devoted to low-income residents can receive tax-exempt financing. During the years prior to the housing crash, when interest rates were significantly higher, that tax exemption could knock a few points off the effective interest rates paid by the borrower. Today, with rates at all-time lows, the economic benefit of tax-exemption is much lower. Building off of Mr. Kotin’s observation, we suggest that it’s possible this effect could be offset by direct support from local cities, counties, or the state, allowing them to subsidize a larger share of the project’s financing costs in return for construction of affordable units.

There are a number of potential funding sources for these subsidies aside from the Affordable Housing Trust Fund. The state has dedicated a significant share of its cap-and-trade revenues to funding transit-oriented affordable housing, including upwards of $200 million expected to be raised in 2015; with about 1/10th of the state population and a high poverty rate, Los Angeles will likely be eligible for at least $20 million from that fund on an annual basis. The city could also offer property tax rebates to density bonus projects with a financial gap, just as they do with hotel subsidies. The upshot to a program like this is that it would require no up-front public expenditures: The developer would build the project with a promise from the city, and only if the anticipated financial gap were borne out would we pay them back with a break on their property tax bill. If the project was more profitable than expected, the property tax break could disappear entirely.

Any program—not just the property tax exemption—could implement controls and clawback mechanisms to recover excessive affordable housing subsidies. Just as with the reduced threshold program proposed in Part 2, if the city contributes $50,000 per affordable unit to fill a financial gap, they can recover those funds from the developer’s profits beyond a certain threshold. The up-front subsidy in all of these examples represents the most that the city would end up paying to subsidize each unit; if the project is more successful than expected, the total subsidy could decline to essentially nothing. Regardless of the developer’s financial outcome, the city increases its supply of affordable housing at minimal public cost.

By taking a comprehensive approach to funding affordable housing, it should be possible to better leverage limited public funds and have a greater share of our affordable housing built with private investment, “buying” affordable units for $50,000 each, or even less. With our next recommendation, in Part 4, we’re headed in a slightly different direction and looking at some recent neighborhood plans that have taken advantage of rezonings, using them to capture new value for the community and potentially provide a significant increase in privately-funded affordable housing.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

*The $350,000 affordable unit cost is assumed for illustrative purposes. Although it is a rough approximation of the current average unit cost for affordable housing, the actual cost can vary significantly between projects.

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.