This is Part 2 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

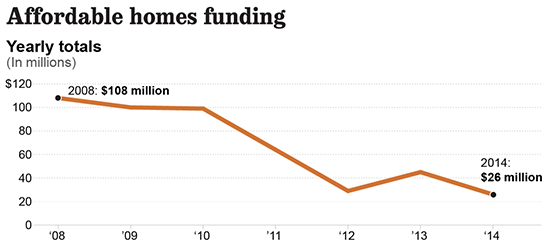

In Part 1 of this series we discussed some of the background of the density bonus program, how it works, and how it’s fallen short in recent years. One of the key observations identified in the LA Business Council Institute’s recent LA River Report is that only approximately 5 percent of the multifamily units built between 2008 and 2013 were affordable units constructed through the density bonus program—roughly half of what we would expect with full participation. This shortfall costs the city hundreds of affordable units each year, and even more market-rate units, which also play a role in moderating rent increases by absorbing some of the tremendous demand for homes in the Los Angeles market.

Here in Part 2 of the series we begin with our specific proposals/recommendations for improving the density bonus program and increasing the supply of affordable housing in the region. So let’s get started!

Proposal: Reduce thresholds to improve program participation.

The idea behind this proposal is that it’s better to have 50 percent of something than 100 percent of nothing, and, on many density bonus-eligible projects, we’re getting no affordable housing whatsoever. By our estimate only about half of the density bonus units that could be built are actually getting built, for a variety of reasons, and this is significantly reducing the supply of both affordable and market-rate units. Raising participation rates to 100 percent (or as close to it as reasonably possible) should be a priority, and that goal is worth pursuing even if it means reducing the share of affordable units at each individual project.

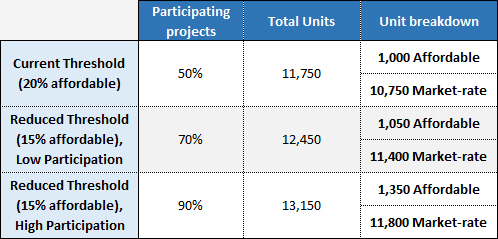

To put this idea in more concrete terms, imagine two alternative scenarios in which 100 new multifamily buildings are constructed in a year, each with 100 units (base, before the density bonus): In one scenario, 50 of those projects take full advantage of the existing density bonus program and set aside 20 percent of their units as affordable to low income households—those earning 50-80 percent of Area Median Income. This 50 percent participation rate seems to be roughly where we stand today in Los Angeles. In this scenario we end up with 1,000 affordable units and 10,750 market-rate units. (50 buildings with 20 Low Income units and 115 market-rate units, plus 50 buildings with 100 market-rate units.)

In an alternative scenario, the rules are changed such that a 35-percent increase in density is allowed when the developer makes just 15 percent of units affordable to low income households, instead of 20 percent. Here, if 70 percent of developers utilize the program we end up with 1,050 units of affordable housing and 11,400 market-rate units; at 90 percent participation, both numbers increase even further, to 1,350 and 11,800, respectively. By lowering the threshold, there is actually potential to increase the supply of both market-rate and affordable, income-restricted units. Whether such a change would increase participation rates to these levels, or even beyond 90 percent, is open for debate. It’s a debate we should have.

Despite the potential for this to be a win-win scenario for both the city and developers, some might be concerned that this could result in a giveaway to developers. After all, some builders are already taking full advantage of the density bonus and setting aside 20 percent of their units for Low Income residents or 11 percent for Very Low Income residents. For those developers, reducing the threshold does nothing but pad their profits while reducing the total amount of on-site affordable housing. We would caution readers to put the needs of our low-income residents (more affordable housing) above whatever personal anti-developer sentiment they may hold—especially when there is no additional public expenditure—but we respect the fiscally conservative approach and think that the updated density bonus program could be structured to minimize these giveaways.

One way to limit handouts would be to make the reduced threshold program a separate, alternative density bonus, rather than a replacement for the current law. Developers could choose to build up to 20 percent Low Income units under the current program structure, as some do now, or they could take advantage of the reduced threshold—with strings attached. Developers that participated in the reduced threshold program would be subject to a clawback mechanism that shared with the city some of the profit earned beyond a certain level. The clawback amount would be limited, of course, to roughly the value of the reduction in affordable units in the project, so as not to discourage developer participation. To illustrate this idea: If a developer opts to provide 15 affordable units under the reduced threshold program (instead of 20 under the current program) they would be required to share with the city a portion of their profits beyond a 15 percent rate of return, up to $300,000 (for example) for each of the 5 affordable units they didn’t build. If the developer makes a lot of money, the city gets paid back and can fund more affordable housing elsewhere; if the developer loses money, or earns a poor return, the city gets no money but it does get the 15 affordable units. Either way, the city gets a significant amount of affordable housing that may not have otherwise been built.

As we hope to have made clear, tinkering with thresholds and adding a clawback mechanism to the density bonus could help us increase program participation and create more housing for residents at all income levels, making the most of private investment and capturing public value wherever possible. This is just the first of many ideas we have for the density bonus and other policies related to development in Los Angeles, and we look forward to sharing more in the coming days. Stay tuned for Parts 3 through 5!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.